This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Ed Fast, November 18, 2025

In a recent Toronto Star column, David Olive called for renewed economic engagement with China. He argued that Canada can hedge against an unpredictable United States by deepening trade with Beijing. But, while diversification is a worthy goal, his prescription is strategically naïve and economically risky.

The idea that Canada can meaningfully “diversify away” from the United States defies geography, history, and common sense. Our two economies are bound by the world’s longest undefended border, a shared language and legal tradition, and deeply integrated supply chains. A whopping 77 percent of the goods Canada exports today are bound to the U.S. No other country receives more than 5 percent of our goods. Canadians and Americans study, invest, and innovate together. It’s not just proximity that matters, but compatibility. Both nations are rooted in democracy, human rights, and the rule of law—principles that underpin investment certainty and regulatory predictability. To pretend that Canada can pivot away from this reality long-term is pure fantasy.

That doesn’t mean diversification is unwise. Strengthening ties with like-minded partners—through our trade agreements with the European Union, South Korea, or through the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—builds resilience without compromising our principles. True diversification extends our reach while reinforcing our values, not undermining them.

Olive understates the profound obstacles to “restoring relations” with China. They are not mere irritants, but deep incompatibilities between Canada’s democratic values and Beijing’s authoritarian conduct. Since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has gamed the rules of global commerce by propping up state-owned enterprises, dumping subsidized products, and weaponizing non-tariff barriers against its critics. Its human-rights record at home and abroad is appalling. Domestically, the persecution of Uyghurs, Tibetans, Falun Gong practitioners, and underground Christians; the crushing of Hong Kong’s freedoms must not be ignored.

Here in Canada, the election interference and the intimidation of Chinese-Canadians through fake police stations should not be overlooked. Not to mention the imprisonment of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor for 1,019 days on fabricated espionage charges. To gloss over these realities is to erode the moral foundation of our foreign policy.

Deeper economic engagement with China would also distort Canada’s trade alignment with our indispensable ally and neighbour, the United States. The moment Ottawa leans too far toward Beijing, Washington will notice—and the response will be swift. With the mandated CUSMA review approaching in 2026, even the perception that Canada is hedging its bets could provoke retaliation through more tariffs, expanded Buy-American rules, or border slowdowns. The result would be lost jobs, investment flight, and diminished trust within North America’s most integrated economic space.

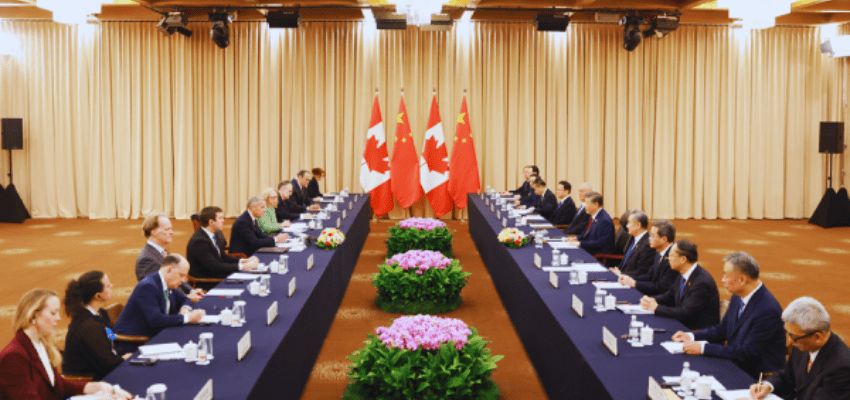

In this context, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s recent meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the APEC Summit—described in Ottawa’s official read-out as a “turning point” in bilateral relations—raises legitimate concerns that Canada may be inching toward renewed accommodation with Beijing. While dialogue is necessary, framing the encounter as a turning point risks signalling to Washington and our allies that Canada is again prioritizing commercial re-engagement over strategic caution.

Any perception that Ottawa is softening its stance on China could be read as a quiet decoupling from our most vital partner, a move that would endanger not only supply chains and investment confidence but the trust on which our North American alliance depends. In a world increasingly defined by geopolitical blocs, even the appearance of hedging between China and the United States invites peril far greater than any short-term economic gain.

Equally troubling is China’s record of weaponizing trade to achieve political ends. Beijing has perfected the art of economic punishment. When Australia called for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19, China responded with crushing tariffs and import bans on Australian wine, barley, and coal. Norway’s salmon exports were blocked after the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo. And when Canada, acting on a lawful U.S. extradition request, detained Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, Beijing retaliated by imprisoning two innocent Canadians and restricting imports of Canadian canola, pork, and seafood.

Most recently, China has pressured Ottawa to lift tariffs on dumped Chinese-made electric vehicles by imposing new barriers on Canadian agri-food exports. This is not the behaviour of a trusted trading partner—it is economic coercion, pure and simple.

Perspective matters. In 2024, Canada’s trade in goods and services with China totalled roughly $130 billion CAD, while trade with the United States reached $1.25 trillion—10 times larger. That massive gap tells the real story: Canada’s prosperity lives and dies with continental trade. Diversification remains sensible, but it must reinforce, not replace, our North American foundation. The smart path forward is to deepen ties with reliable democracies in Asia, Europe, and Latin America while safeguarding our primary partnership with the U.S.

Calls to resume free-trade negotiations with China are particularly misguided. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper purposely declined to negotiate a free trade agreement with China. Although the Trudeau Liberals abruptly reversed course, talks were eventually suspended for good reason. Beijing’s pattern of ignoring the spirit and letter of its trade commitments makes enforcement nearly impossible.

Australia and New Zealand both have free-trade agreements with China, yet each has faced arbitrary import bans and politically motivated boycotts whenever they displease Beijing. A Canadian agreement would offer the same illusion of access but no meaningful protection—binding us to an unreliable partner while undermining confidence in our own adherence to democratic norms.

None of this argues for isolation. Constructive engagement remains essential on issues of global consequence—climate change, public health, nuclear proliferation—but such cooperation must rest on clear boundaries and mutual respect. Canada should work with allies to build secure supply chains for critical minerals, strengthen our defences against cyber and economic coercion, and ensure that trade with China occurs on transparent, rules-based terms. Engagement, yes—but in good faith.

For centuries, China has viewed itself as the “Middle Kingdom,” destined to draw other nations into its orbit. Today’s Belt and Road Initiative, state-directed investment, and industrial subsidies flow from that worldview. To engage China effectively, Canada must see it as it is: authoritarian, expansionist, mercantilist, and determined to bend the rules to its advantage. Beijing seeks influence, not partnership; deference, not reciprocity; dependence, not mutual benefit.

A clear-eyed Canada would pursue a pragmatic middle course by rebuilding trust with Washington, broadening trade with fellow democracies, and engaging China selectively while safeguarding our sovereignty and values.

While it is true that under Donald Trump the United States has itself become a more unpredictable and, at times, more protectionist partner, this volatility is likely to be a short- or medium-term political reality rather than a structural one. In the long run, Canada’s interests are still most secure within a continental partnership rooted in democratic institutions, the rule of law, and broadly free-market principles.

Unlike China’s predatory, state-driven, and authoritarian model, the U.S. system—despite episodic turbulence—remains fundamentally aligned with Canada’s values and long-term economic aspirations.

As the world fractures into competing spheres of influence, Canada’s strength lies not in appeasing authoritarian giants but in deepening bonds with nations that share our ideals. Calls for renewed intimacy with China may sound bold, but they mistake opportunity for risk. Canada’s prosperity and principles will always rest first and foremost with the friends who play by the rules.

Ed Fast is a former Minister of International Trade and Distinguished Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Center for North American Prosperity and Security.