This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Laura Dawson, May 20, 2025

At George’s Diner in Waco, Texas, I learned that trade and migration look a whole lot different from the U.S. southern border with Mexico than from the northern border with Canada.

It’s not a red light versus green light situation where the state is either open or closed to travel and trade. Rather, it is highly specific depending on who (or what) is crossing the border. Those who follow the rules are welcome, but those who do not should be excluded.

In early April 2025, I met with a group of farmers and ranchers in Waco to talk about trade and borders. Over eggs and coffee, they talked me through positions that were both nuanced and persuasive.

The first thing I learned is that unauthorized immigration is not just a problem in Texas—it’s a crisis. Texans are willing to do anything to reduce the surges of people and violence that accompany these surges.

Secondly, almost everyone agrees that international trade is good for Texas, but businesspeople want to reset an international trading system that doesn’t make sense to them, where “we follow the rules and China never seems to.”

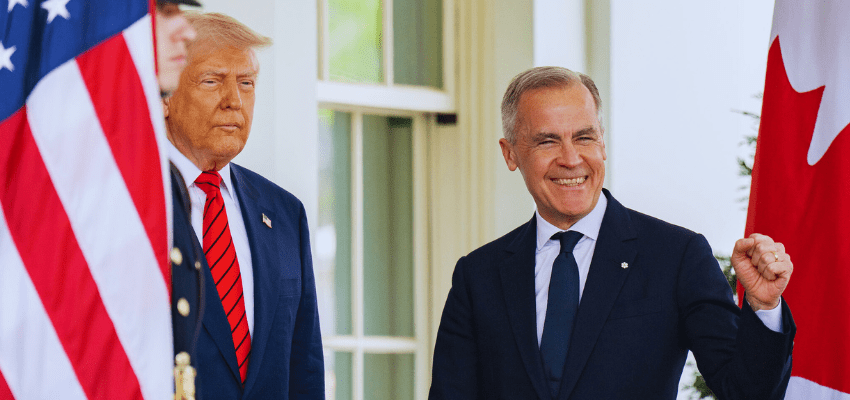

A third message that came across loud and clear in the land of the longhorn is that Canada is a respected neighbour, a sovereign state, and a valued trading partner. The 51st state messaging did not reflect the views of any Texan I met. The fact that they are allowed to stand is, I believe, a regrettable byproduct of a population pushed to the limit on a few key issues.

Geography is the dominant factor in explaining how the migration crisis hits down here. About half of the U.S.-Mexico border is in Texas. Much of the borderland runs across family ranches and farms. Locals tell stories about finding bodies on their land or migrants inside their homes ransacking the fridge. There is sympathy for the individuals seeking better lives for themselves, but not for the organized criminal networks managing the human smuggling routes.

“The ironic thing,” noted one of the farmers, “Is that we are desperate for agricultural workers, but the migrants coming through here just pass us by on their way to the cities.”

For Texans, it is impossible to look the other way on unauthorized migration. It’s in their face every single day, interrupting legitimate travel and trade, and bringing violence to small, rural communities. In the Del Rio region, parents can’t leave their teenagers alone in the house because groups of 20 to 50 migrants pass within yards of the family home every single day. Break-ins in search of water and supplies are a regular occurrence. In a video put out by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, Donna Schuster, a rancher from Becketville, Texas, explains that she can’t walk from her house to the barn without carrying a gun. Says Shuster, “We are fearful and afraid in our own homes.”

In 2023, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported nearly 400,000 migrant encounters in the Texas Del Rio sector. Compare this to some 7000 encounters in the Swanton sector between Ottawa and Montreal, where most of Canada’s unauthorized migrant encounters take place. Recall the sense of outrage many Canadians felt about migrants jumping the line at Roxham Road south of Montreal. Imagine how it feels to live in Eagle Pass, Texas. This city of 28,000 people recorded 16,000 migrant encounters in a single day in 2023, overwhelming both border officials and local authorities.

The Texans I spoke to were united in the belief that Mexican cartels benefit the most from U.S. inaction on migration. Borderland residents are furious that they no longer feel secure in their homes, even as Americans in other parts of the country debate endlessly about legal niceties and partisan politics. It seems to me that this is the main reason why so many Texas voters were willing to give President Trump the votes he asked for to crack down on the cartels.

During a week of meetings with Texas business and trade organizations, I was struck by the consistency of their message. Whether I was speaking to ranchers, manufacturers, or state officials, they are fed up with the stranglehold the cartels have over the illicit movement of people and drugs and are demanding that their elected representatives deal with the problem once and for all.

The big challenge is how to do this and also support the flow of legitimate trade. As someone who runs a Canada-U.S. business organization, I have spent time in almost every state in the U.S. Without a doubt, Texas is one of the most trade-forward states I have ever visited. The people recognize real growth as a result of NAFTA and USMCA. Since 1994, Texas trade with Mexico has increased by more than 600 percent. It has become the top exporting state in the U.S., generating globally competitive positions in energy, agriculture, technology, and manufacturing. About a third of all U.S. trade with Mexico passes through Texas.

It’s complicated

Texas has a complex relationship with Mexico and Mexicans. You have to be clear about what aspect of Mexico you are talking about, because the relationship is different in different contexts. Are you talking about Mexico’s complementary manufacturing base and large consumer market that drive Texas prosperity? Or, are you talking about Mexican cartels that have a hand in every form of illegality found in Texas, from narco-trafficking and human smuggling to illicit trade and official corruption?

It’s important to remember that, when you’re talking about Mexicans in Texas, you’re not talking about foreigners. Like the U.S. and Canada, it’s a sibling relationship.

Mexicans were living in Texas before there was a border, and there are deep Tex-Mex cultural roots in every community. At 31.3 million people, the population of Texas is a little less than Canada’s. Approximately 39 percent of Texans are Hispanic, and about 33 percent of these claim Mexican origin, making it the state’s largest demographic group. People in Texas don’t resent Mexicans. They are brothers, sisters, and cousins. Every city and town in Texas celebrates numerous Mexican cultural days, including Día de los Muertos and Cinco de Mayo. In Corpus Christi, you can visit a museum honouring the life of slain Tejana music superstar Selena Quintanilla.

What Texans resent are criminals, rule breakers, and those who misuse the rights of lawful passage of people and cargo across the border. Many of the people who complained to me about the cartels were themselves of Mexican descent. In the 2024 presidential election, Donald Trump won 14 out of 18 counties within 20 miles of the border, doubling his 2020 performance in the Latino-majority region. Notably, he secured 58 percent of the vote in Starr County, which is approximately 97 percent Hispanic, marking the first time a Republican won there since 1892.

Anger at the prevalence of cartel activity is amplified by the tragedies of the opioid crisis. Everyone I met had a personal story about how opioids affected them.

“Eight kids died at my son’s school this year alone,” said one. “My brother-in-law,” said another. To counter this very personal scourge, Texas gave the president their vote in the hopes that he could stop the dying.

Even though my trip was about bridging gaps in knowledge between Canada and Texas, I was reluctant, in these circumstances, to point out that fentanyl flows from Canada to the U.S. are exceedingly small. Especially since I know full well that the organized criminals manufacturing and distributing fentanyl north of the border are affiliates of the criminal networks on the southern border. While “Canadian” fentanyl is not moving in high volumes into the U.S. (it largely remains in Canada for domestic consumption), that does not mean that fentanyl is not a shared crisis, demanding shared intervention.

One of the things that struck me about Waco is how much it reminded me of small-town Alberta—hard-working, friendly people doing the best they can against politics that never seem to be going their way. One of the first things most people said when they met me was to apologize for the 51st state remarks and reaffirm their respect for Canada and Canadians.

The farmers from George’s Diner recognized that the Texas economy has a mutually beneficial relationship with Canada. As their second largest trading partner after Mexico, Canada is a source of potash for fertilizer, crude oil for Texas refineries, and Canadians buy more than $36 billion a year from Texas. Such exchanges make both places stronger. The ranchers’ group plans to take a trip to Alberta this summer for the Calgary Stampede, and they want to see the oil sands. I warned them that they might not receive the warmest welcome in Canada, but they were eager to go anyway, engage in a little person-to-person diplomacy, and try to mend some fences. (They’re farmers, they’re good at that.)

We’re better together

During my meetings with Texas businesses, it was hard to get a clear explanation for the inconsistencies between productive trade relations with allies like Canada and the global tariff war launched by the White House. One veteran business lobbyist explained it to me this way: “President Trump is a poker player, and the stakes for Texas are high. So we’re willing to give him some time to play his hand and make the kind of changes we need around here.”

Everyone I met presented some ideas I could agree with, even if I couldn’t agree with all of the tactics being employed. One political consultant argued, “We need a radical overhaul of the international trading system or we’re all going to end up living on Planet China.” This is valid—up to a point. No one had anticipated China’s market strength, its ability to make almost everything cheaper than we can in North America, nor its ability to exploit the loopholes and unintended consequences enmeshed in WTO trade rules. But targeting China with anything other than surgical precision risks alienating a lot of U.S. allies and taking down the entire global trading system at the same time.

My career has been dedicated to strengthening North America’s economic prosperity through cooperation, so America’s go-it-alone approach is not something I agree with. I remain firmly convinced that we are better together. But how do you level the playing field and make rules fairer for manufacturers in Texas (and Laval and Windsor) without breaking the carefully constructed Jenga tower that is the system of international trade rules? I’m not sure any of us has a good answer for that one.

The notion that you can make everything in the United States and import nothing is a compelling political slogan, but anyone who works on a cross-border supply chain will tell you that locals-only manufacturing sacrifices access to affordably priced inputs and a global consumer base. What’s more, the time and money required to construct new domestic manufacturing plants would stall the U.S. economy for years.

The fracturing of established supply chains and the costs of compliance with shifting tariff rates were hitting the Texas manufacturers I met hard. Some are losing millions of dollars a week from already thin profit margins. Armies of customs specialists are spending hours every day doing paperwork to certify that every component in their finished product meets USMCA-origin requirements (about 60 percent North American content for most goods and 75 percent for automotive products). In Dallas, a trade compliance manager I spoke to admitted that she never thought she would be spending her days calling up steel mills to verify the origin and processing method of the metal contained in a perfume cap.

In the past, for products requiring a lot of different component parts, manufacturers would avoid the USMCA-origin paperwork and import some of the inputs using the WTO Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) rate, usually under 5 percent, which could be applied to virtually every product in the global trading system. However, under the reciprocal tariff rates announced by the president, every country has a different tariff rate for its goods entering the United States, many of which are higher than 10 percent. This new system effectively nullifies the MFN option for importers and creates mountains of paperwork for importers and border officials.

What’s next for world trade?

In a period of shifting uncertainty, it’s not clear what the new global trading system will eventually look like. Will there be one set of rules for trade with the United States, and the rest of the world will continue to use the WTO system? Or will the WTO rules continue to fracture without the leadership of the U.S. to encourage compliance by others? For now, the USMCA/CUSMA rules continue to hold — meaning that Canada and Mexico are largely exempt from many of the new tariffs, if they can figure out the origin paperwork.

In Texas, they recognize the value of the trilateral trade deal not just as a tool for growth but also as a hedge against China. One Texas business leader pointed out that under the old NAFTA system, China had been the U.S.’ number one trading partner (mostly due to high import volumes by the U.S.), but the tougher origin rules in the USMCA meant that China had dropped down to number three position after Mexico and Canada — evidence that regional reshoring efforts can make a difference.

All in all, there is a clear consensus in Texas about the importance of reforms to migration that include strict border measures but also a path to citizenship for workers with skills and no criminal ties. But on the issue of trade, there is consensus on the starting point: Trade with Canada and Mexico is good, but China has distorted the system, shifting benefits away from the U.S. What is not clear is what sort of reforms will work to reduce dependence on China while preserving trade relationships with partners like Canada.

What can Canada learn from Texas?

Texas is a state where ideas and cultures, people, and businesses intersect and sometimes collide. But rather than fall apart, Texans are strengthened by their diversity. The key to their success seems to be a willingness to tolerate a certain amount of ambiguity but also to fight against the things they can no longer endure.

Ten years ago, I remember having a coffee with an elderly couple with a ranch on the southern border. They left caches of water on their property because they hated to find dead bodies on their land. They were staunch Republicans and couldn’t understand why Washington was ignoring the migration crisis. They finally found a president willing to deal with their issue, but this action has come at a cost.

Canadians trying to maintain or build their business relationships in Texas need to understand that the state’s relationship with the White House is complicated. On issues such as border security and infrastructure, the state has often had to step in to fill gaps left by the feds. With a White House finally able to push down the numbers of unauthorized migrants, Texans are willing to keep their powder dry on other issues.

But, as their relationship with Mexico shows, Texans are able to handle complexity and nuance in their relationships. Texans think well of Canada, but right now, we’re not on their radar screen. There is a certain amount of awareness that deeply discounted Alberta crude feeds highly profitable Texas refineries, but few Texans are aware of Canada’s extraordinary levels of public and private sector investment—estimated at more than $100 billion.

The Government of Canada has not pursued an aggressive media campaign to counter misinformation in the U.S. When the White House began to push out message about unfair Canadian traders, there were a few attempts to push back on U.S. mainstream media, but nothing to counter the barrage of bogus social media posts claiming about Canadian tariffs. Business organizations promoting Mexican, South Korean, French, and British business relationships are found in every city in the U.S. By my count, there are fewer than five Canadian business advocacy organizations in the whole of the United States.

We need to understand that the Canada-U.S. relationship—like the Texas-Mexico relationship—is characterized by a lot of mixed feelings. We are also brothers, sisters, and cousins, capable of bitter misunderstandings but also reconciliation. Like Texas, Canadians with business ties to the U.S. have to think about the long game and exercise patience where possible. You can’t be angry and smart at the same time.

It is clear that the Canada-U.S. relationship is changing. Temperatures are hot and elbows are up, but real progress calls for strategic re-evaluation of interests and opportunities, not rash action. Our future relationship depends on keeping the lines of communication open and mending fences when necessary. These are the lessons I learned at George’s Diner.