This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Tim Sargent, August 1, 2025

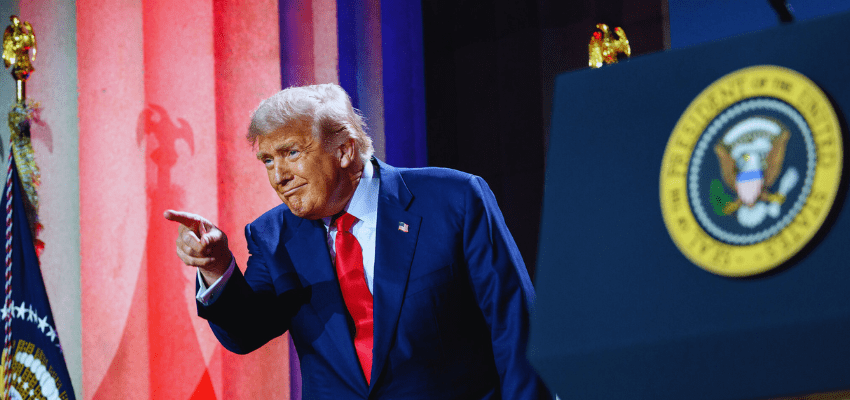

President Trump’s August 1 trade deal deadline has come, and still, there is no agreement between the U.S. and Canada (or with Mexico). Instead, Trump has raised tariffs on Canada from 25 percent to 35 percent, ostensibly for our lack of action on fentanyl smuggling.

Should we worry? Would it have been better if we had swallowed our pride and followed Japan and the EU by conceding permanently higher across-the-board tariffs (along with promises to invest in the U.S. and to buy more U.S. products) in exchange for somewhat lower tariffs on sectors like autos?

No, it would not. Canada is in a stronger position than it appears, and our position will only get stronger over time.

At first sight, this statement seems counterintuitive. While U.S. exports to Canada are a very small share of its economy—equivalent to only 1.5 percent of U.S. GDP—Canadian exports to the U.S. are very significant, accounting for 22.8 percent of our GDP. This is a much higher share than any of the U.S.’s other major trading partners, except for Mexico. In the face of this disparity, it may seem that the U.S. holds all the cards in any negotiation.

However, the reason why exports to the U.S. are such a large part of our economy is that our economic relationship with the U.S. is very different from that of the EU, Japan, or China.

Rather than just shipping finished products to the U.S., we also sell raw materials and intermediate goods that U.S. companies turn into finished products. In fact, Canada is a key supplier to the U.S.: our potash enables American farmers to grow food, and our electricity and lumber enable American businesses to power factories and build homes. While in some cases alternative sources are available, these will usually come at a greater cost because products goods to be shipped from much farther away.

This intertwining of our two economies means that even the finished goods that we export to the U.S. have significant U.S. content: for example, Canadian-produced autos typically have about 50 percent U.S. content.

As a result, whether Trump likes it or not, Canada (and Mexico) are an integral part of “Factory North America”: a U.S.-led (and mostly U.S.-owned) continental economy.

It does seem that Trump understands this co-dependency. After every threat to impose high overall tariffs on Canada and Mexico there follows a “clarification” from some unnamed official in the administration that the tariffs only apply to non-CUSMA compliant goods, which are a small portion of our exports, typically those that don’t meet CUSMA rules of origin, which means that there is little Canadian value added. Auto parts are exempted from the Section 232 tariffs on autos, as is the value of U.S.-produced parts in a finished vehicle, which takes much of the sting out of these tariffs.

The alternative, a point that I suspect has been made forcefully to Trump by U.S. companies, is economic chaos as whole supply chains are disrupted and costs spiral unpredictably across the North American economy.

And with most of our exports shielded from tariffs, the imposition of tariffs on America’s other trading partners means that Canadian exporters are now in a better competitive position vis-à-vis their foreign competitors.

Furthermore, time is not on Trump’s side.

Up to now, the various tariffs he has imposed have not had much impact on consumer prices, as companies have been waiting for the current uncertainty before passing on price increases. However, companies cannot do this indefinitely, and with tariff “deals” now in place with most of America’s main importing countries, we are likely to see significant increases in consumer prices in the next few quarters.

Trump’s tariffs are already not particularly popular amongst the U.S. electorate, and higher prices (and potentially higher interest rates) are not going to change that perception. With only 15 months until the 2026 midterm elections, Trump will have to tread carefully if he is not to lose the Republicans their majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Even when it comes to the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, which Trump sees as central to his vision of revitalising manufacturing in the U.S., there are indications that the administration is starting to recognize that high tariffs mean higher costs for American users of steel and aluminum, particularly in the auto industry, which will add additional pressure to prices.

In addition, Trump is on shaky legal ground when it comes to legal authority for his across-the-board tariffs: the so-called reciprocal tariffs on most of America’s trading partners, and the so-called fentanyl tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China. These tariffs—unlike the sectoral tariffs on steel, aluminum, and autos—are imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a 1977 law which has been mainly used to impose sanctions, and which has never before been used to implement tariffs. The Trump administration has already lost one court challenge, and while that decision was stayed pending an appeal, it is quite possible that the tariffs will ultimately be found unconstitutional.

As a result, Canada has every reason to play for time. Trump is in a hurry because he needs to be; our incentives are the exact opposite. Furthermore, with CUSMA coming up for renewal next year, we should avoid making concessions now when the U.S. will soon be coming back for more.

This does not mean that we can afford to be complacent. Tariffs on autos, steel, and aluminum are likely to remain at elevated levels so long as Trump is president, and as a country, we will need to think hard about the viability of an economic model that is heavily dependent on the auto sector.

Our geographical proximity to the world’s largest and most vibrant economy remains a precious economic asset, but we can no longer take it for granted. We will have to play our cards carefully in the months and years to come.