This article originally appeared in Policy Magazine.

By Fen Osler Hampson, Tim Sargent and John Weekes, July 25, 2025

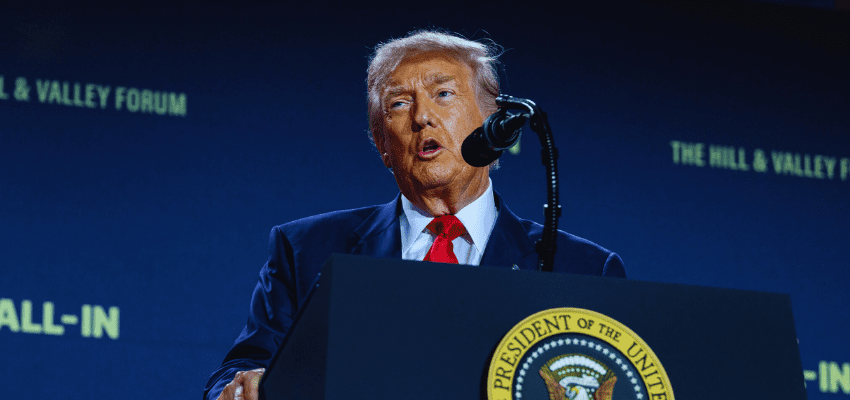

President Donald Trump’s 15% tariff deal with Japan has laid bare the utter chaos of Washington’s tariff war. The big three automakers—General Motors, Ford and Stellantis—which have already taken a big hit from Trump’s 25% tariffs against Canada and Mexico are crying foul, saying that that the agreement puts them at a competitive disadvantage against Japanese automakers, which it clearly does.

The situation will be made a lot worse if there is no deal with Canada and Mexico by the August 1st deadline when both countries will be slapped with 35% and 30% percent tariffs, respectively.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has already warned Canadians that there may be no deal before that deadline. Canada-US Trade Minister Dominic Leblanc — who along with Canada’s Ambassador to the US Kirsten Hillman met with US officials this week — has warned that there is still “a lot of work” to do to get there.

So, what’s the game plan? It should be pretty clear from Trump’s statements and those of his senior officials that the goal is to bring both auto and high-value auto parts manufacturing back to the US, even if that means shutting down plants in Canada and Mexico, destroying the integrated value chains that have lowered costs for American consumers and made North American production highly efficient to the shared advantage of all three countries.

However, this is not the only concern we face. Canada’s supply management system for dairy and poultry remains a significant and longstanding point of bilateral contention, predating Donald Trump’s second term. Bill C-282, which enjoys support from all political parties, removes supply management from the scope of trade negotiations.

There is a real and understandable worry in Western Canada that if Ottawa refuses to reduce tariffs and increase quotas in dairy and poultry due to the restrictions in Bill C-282, exports of beef, grains (wheat, canola, barley), and other agricultural products might suffer as a direct consequence of US retaliation.

Should the US respond to Canada’s stance by boycotting its agricultural exports or imposing punitive tariffs, the resulting economic impact would be severe.

Our preliminary analysis of the GDP losses of auto assembly and engine manufacturing in Canada and the pain of a retaliatory escalation in agricultural exports, based on the protection of supply management as a deal-breaking sacred cow, indicates about $15 billion CAD in lost automotive GDP contribution and another roughly $12 billion from agriculture, with roughly 180,000 direct jobs at risk.

If we further retaliated by banning American foodstuff imports and scrambled to replace them with imports from Latin America, Europe, or Asia, the net hit to GDP climbs to about $26 billion CAD in the first year, or roughly 1% of the nation’s total output. In human terms, that translates to an additional 10,000 or more jobs lost elsewhere in the economy as food supply chains realign.

To be clear, these are back-of-the-envelope calculations, but the overall direction is instructive. There is no denying the economic blow or the personal hardship the shutdown of our auto sector and a retaliatory US embargo on our agricultural exports, because of our refusal to budge on supply management, would inflict.

In this pro forma scenario, Canada would likely pivot to buying vehicles from Korea, Japan, China and Europe. The one small silver lining is that Canadian consumers would gain billions in savings from significantly lower-cost models, especially from China—roughly $3 billion or more in extra consumer surplus as automakers elsewhere fill the void of Detroit’s Big Three.

Food imports would become a lot costlier, however, although prices would eventually stabilize as ports and logistics infrastructure scaled up over several years.

Meanwhile, the industries most affected by punitive US auto tariffs would look to new markets in Asia and Europe, retooling their plants and retraining some of their workforce. However, these processes take time, as workers move into new sectors and factories and capital are redeployed, perhaps toward high-tech manufacturing, food processing, or advanced “smart agriculture” for export.

Within three to five years, our preliminary estimates suggest that the GDP impact would likely narrow to somewhere between 0.3% and 0.5% below the previous baseline. Within six to ten years, especially if trade agreements with Asia and Europe bear fruit, the Canadian economy could plausibly rebound to pre-shock levels.

New opportunities could also present themselves, such as growth in logistics, ports and EV infrastructure; innovation in food technology, and a broader set of trade partnerships. History has shown that supply chain shocks, while often very painful, can generate growth and productivity as industries adapt.

But the political backlash from disrupted sectors in this scenario would be severe and the cost of living would invariably rise until new food import channels were established. The rupture with the US in automobile manufacturing and trade, a key sector of our economy, would leave lasting scars.

The upshot is that the federal government should waste no time developing its own rigorous estimates and contingency plans in the event of a major disruption to these two key export sectors of the Canadian economy, if it has not already done so, while making it plain to the Americans and their President that inflicting pain on Canada comes at a reciprocal cost: the US would lose its biggest motor vehicle export market, Canada, which is worth well over 20 billion to the US alone in sales of cars, SUVs, light and heavy trucks.

The US would also jeopardize a substantial portion of its agricultural trade to its second biggest market after Mexico, which is worth roughly $38.5–$40 billion in annual sales (if you include grain and feed exports, processed foods and other consumer-oriented products).

American consumers will pay the costs of this disruption with significantly higher prices while Canadian consumers would end up replacing US goods with those bought elsewhere.

Both countries would become more independent but poorer as a result. Is that really what Trump wants?

Fen Osler Hampson, FRSC, is the Chancellor’s Professor and Professor of International Affairs at Carleton University, and President of the World Refugee & Migration Council. He is Co-Chair of the Expert Group on Canada-US Relations.

Tim Sargent is Director of Domestic Policy and Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa. He was Deputy Minister of Trade during the renegotiation of NAFTA during the first Trump administration.

John Weekes, who was Canada’s chief negotiator for the original NAFTA and ambassador to the WTO, is a member of the Expert Group on Canada-U.S. Relations, and a fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.